Weimar Republic Hyperinflation

2025-03-26By Green Snake

Introduction

Today, I'm going to be talking about hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic (Germany) after World War 1 in 1919.

What is Inflation

If you haven't checked out the previous blog on hyperinflation, check it out here (venezuela hyperinflation)

tldr; paper money gets printed into worthlessness. It takes infinite monopoly money to buy literally anything.

Weimar Inflation

The Weimar Republic faced a brutal defeat in World War 1 (WW1), suffering 2+ million dead, and their economy in ruins. After WW1 in 1919, the Weimar Republic (Germany) was faced with paying off infinite war reparations to the various countries. In order to do this, they had to work the money printers on overtime. During the war, they even abandoned their gold standard, which is a link to reality.

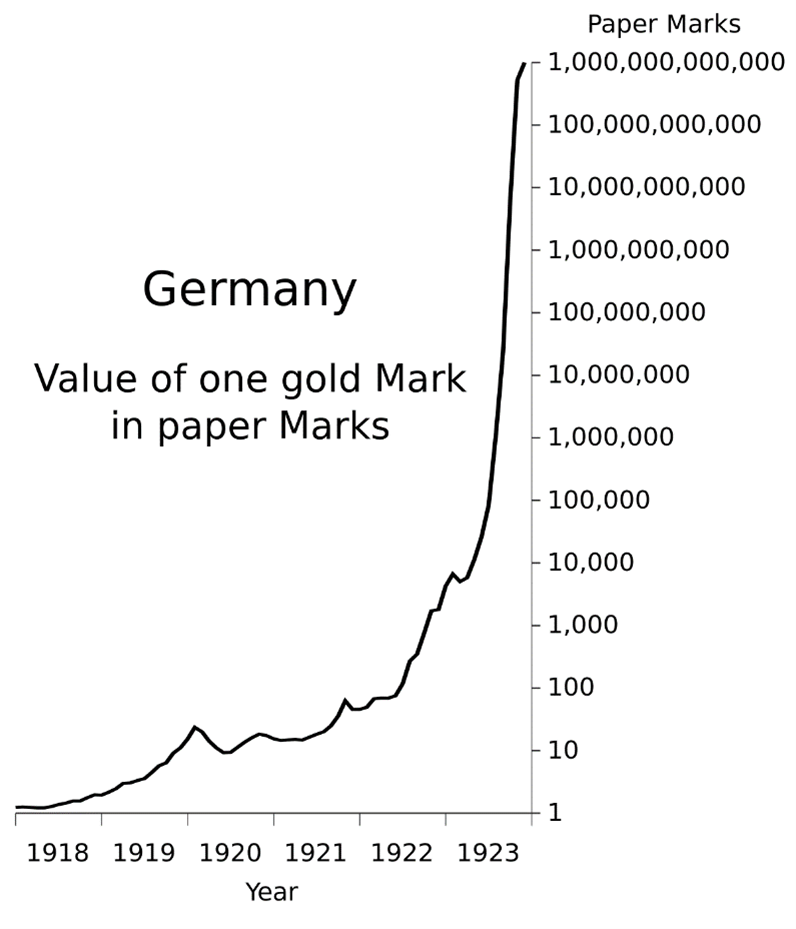

Hyperinflation hit hard after 1923. It was later stabilized with new currency.

Weimar Money

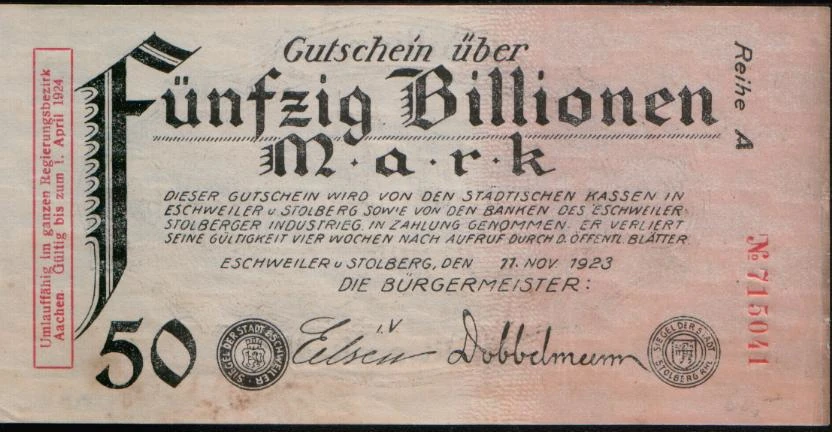

Pictured: 50 trillion marks (not billion).

Note: Milliard = billion.

The Mark was printed into oblivion. In January 1923, a dollar was 17,000 marks and 4.2 trillion marks in December.

To stop the hyperinflation, a new money system was introduced. In late 2023, the Rentenmark was introduced, backed by land. A trillion marks equals 1 Rentenmark, which equals ~$0.23 USD. The Rentenmark was followed by the Reichsmark, which is gold backed. Much later, is coined in silver.

Pictures

Hyperinflationary Journey

Prices would double within a five month period. The monthly inflation at one point was 30,000%. The inflation was so bad, workers would get their bundles of paper money and immediately run home to spend it. Some got paid twice a day. One man went to a cafe. Bought a cup of coffee for 5,000 marks. Then bought another cup and that was 14,000 marks. In Oct 1923, sending a letter cost 15 million marks. Two days later, it would be 30 million marks.

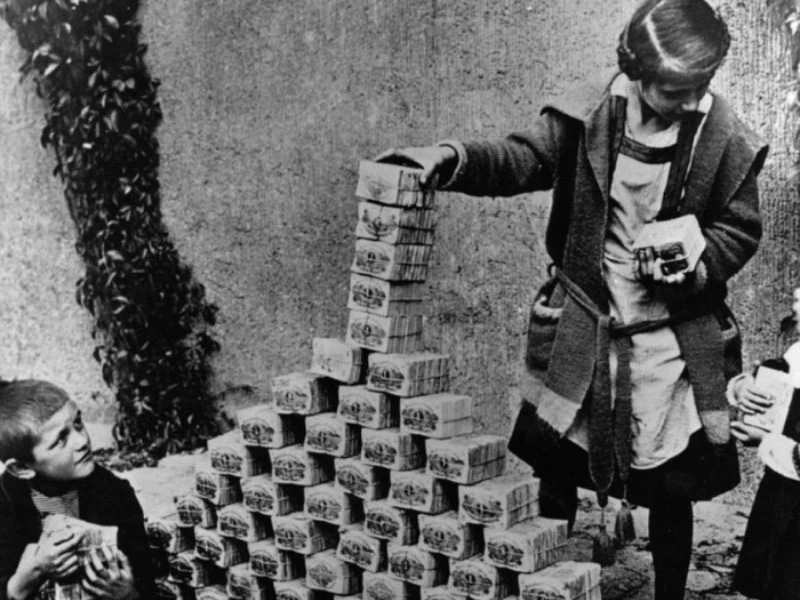

Anyone who had loans were able to pay back the nominal amount with easy to get worthless money. People were using the paper money as wallpaper, heat, and fuel. In 1923, a pound of bread cost around 200 million to 3 billion marks. People who were on fixed income like pensions were paid in worthless paper money.

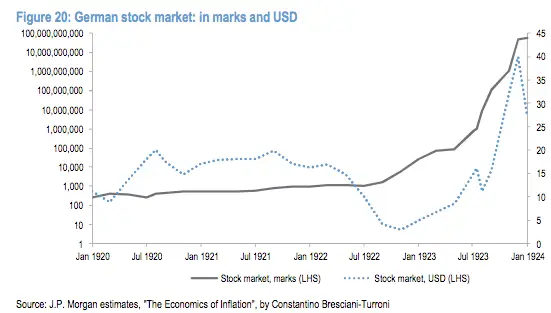

In terms of Marks, the stock market went vertical. Many people lost their fortunes and were thrust into starvation scenarios. People who have to bring a wheelbarrow of paper money just to buy some basic food. In some areas, people resorted to looting and rioting to survive. Some formed armed gangs that even roamed the countryside.

To survive, people were doing literally any work in Berlin. Foreigners find themselves with more purchasing power when they visit.

When Money Dies

Here are some quotes from this interesting book, "When Money Dies" by Adam Fergusson.

Whereas in 1914 it required 80 hours of work to buy a suit of clothes and in 1919 141 hours, by July 1922 381 hours were needed. Similarly, the hours required to buy a dozen eggs had moved from one to three, and for a kilo of bread from half to two. In the countryside the landowners and farmers were less affected than anyone, producing most of their own essentials and putting up commodity prices as regularly as the shopkeepers.

Only the country people were survivng in Germany in any comfort: anyone who lived off the land had the readiest access to real values. It was not surprising that even when they ensured that the money receipts for their goods were no more than equivalent in purchasing power to what they were used to, they were accused of extortion - the more so if they delayed the sales of produce in the full knowledge that prices would be higher the longer they waited.

...that in February 1922, with a loan from a friendly banker, he bought an estate neighbouring his own property in Pomerania for 4 million marks (then equivalent to about £4,500). He paid the debt in the autumn with the sale of less than half the crop of one of his potato fields. In June of the same year, when prices were shooting up ahead of the mark, he bought 100 tons of maize from a dealer for 8 million marks (then about £5,000). A week later, before it was even delivered, he sold the whole load back to the same dealer for double the amount, making 8 million marks without raising a finger. 'With this sum,' he said, 'I furnished the mansion house of my new estate with antique furniture, bought three guns, six suits, and three of the most expensive pairs of shoes in Berlin - and then spent eight days there on the town.'

This was simple commerce: the only thing to do with cash by that time was to turn it into something else as quickly as possible. To save was folly.

Dr Schacht's account of the inflationary years recalled that farmers 'used their paper marks to purchase as quickly as possible all kinds of useful machinery and furniture - and many useless things as well. That was the period in which grand and upright pianos were to be found in the most unmusical households.'

Anyone who was alive to the realities of inflation, he said, could safeguard himself against losses in paper currency by buying assets which would maintain their value: houses, real estate, manufactured goods, raw materials and so forth.

Petty crime, the crime of desperation, was flourishing. Pilfering had of course been rife since the war, but now it began to occur on a larger, commerical scale. Metal plaques on national monuments had to be removed for safe-keeping. The brass bell plates were stolen from the front doors of the British Embassy in Berlin, part of a systematic campaign unpreventable by the police even in the Wilhelmstrasse and Unter den Linden. That members and families of the British Army of the Rhine suffered severely from burglaries probably reflected the fact, not that thieves had particular animus against the forces of occupation, but that these days foreigners were so much more robbable than anyone else. Over most of the Germany the lead was beginning to disappear overnight from roofs. Petrol was syphoned from the tanks of motor cars. Barter was already a usual form of exchange; but now commodities such as brass and fuel were becoming the currency of ordinary purchase and payment.

A cinema seat cost a lump of coal. With a bottle of paraffin one might buy a shirt; with that shirt, the potatoes needed by one's family. Herr von der Osten kept a girlfriend in the provincial capital, for whose room in 1922 he had paid half a pound of butter a month: by the summer of 1923 it was costing him a whole pound.

Communities printed their own money, based on goods, on a certain amount of potatoes, or rye, for instance.

Those with foreign currency, becoming easily the most acceptable paper medium had the greatest scope for finding bargains. The power of the dollar, in particular, far exceeded its nominal rate of exchange. Finding himself with a single dollar bill aerly in 1923, von der Osten got hold of six friends and went to Berlin one evening determined to blow the lot; but early the next morning, long after dinner, and many nightclubs later, they still had change in their pockets. There were stories of Americans in the greatest difficulties in Berlin because no-one had enough marks to change a five-dollar bill: of others who ran up accounts (to be paid off later in depreciated currency) on the strength of even bigger foreign notes which, after meals or services had been obtained, could not be changed; and of foreign students who bought up whole rows of houses out of their allowances.

There were stories of shoppers who found that thieves had stolen the baskets and suitcases in which they carried their money, leaving the money itself behind on the ground; and of life supported by selling every day or so a single tiny link from a long gold crucifix chain.

One used to see the appearance of their flats gradually changing. One remembered where there used to be a picture, or a carpet, or a secretaire. Eventually their rooms would be almost empty - and on paper some people were reduced to nothing. In practice, people didn't just die. They were terrbily hungry, and relations and friends would help with a little food from time to time. We sent them parcels, or took them ourselves because we had no cash to pay for postage. And some of them begged - not in the streets - but by making casual visits...

There was no way to get medical help without money. If you had toothache you couldn't afford a dentist. If you needed to go to hospital, you might get into a convent: otherwise you stayed at home, and got better, or got worse.

The 1922 medical reports had shown that every great town in Germany had substantial pockets of desperate undernourishment. Throughout the urban nation, lack of food, clothing and warmth had produced all their concomitant ailments, from ulcers to rickets, from pneumonia to tuberculosis, all pitifully aggravated by the soaring costs of medicines and medical supplies.

All who were not clever enough to hoard the forbidden stable currencies or gold have, without exception suffered losses.

In hyperinflation, a kilo of potatoes was worth, to some, more than the family silver; a side of pork more than the grand piano.

...theft was preferable to starvation; warmth was finer than honour, clothing more essential than democracy, food more needed than freedom.

Weimar Silver and Gold

At the start of the war, the paper money was no longer redeemable in gold. Literally buying anything but this paper money was a good idea.

From 1919 and five years later, gold went from 170 marks to 87 trillion marks per ounce. Silver went from 12 marks to 544 billion marks per ounce.

For most of the period, the gold/silver ratio was around the historical ~15. One period had it at 160 for a Oct - Nov 1923. Possibly due to the attempted communist takeover that had people turning silver to the lighter gold and fleeing.

(source: mining.com, silver and gold charts)

Conclusion

Many people were blindsided. They suffered with poverty, starvation, and violence. Disillusioned, this set the stage for a radical new government to take over.

References

- When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany- Interesting book by Adam Fergusson.

- Wikipedia of the Hyperinflation in Weimar

- seeking alpha

- American German Institute

- pbs.org

- Smithsonian magazine

- bbc.co.uk

- britannica

- mises.org

- businessinsider.com, weimar stock market